Reactive Programming 4

Observable, Rx

지난시간엔 단일 데이터에 대해 latency 를 지원하는 Future, Promise 에 대해서 알아봤다. 이번에는 컬렉션에서 latency 를 지원하는 방법인 Observable 을 배워보자.

One Many

Synchronous T/Try[T] Iterable[T]

Asynchronous Future[T] Observable[T]

From Futures to Observables

Future 의 정의를 다시 보면,

trait Future[T] {

def onComplete[U](f: Try[T] => U)

(implicit ex: ExecutionContext): Unit

}

여기서 중요한 부분은 콜백 f 를 받아 Unit 을 돌려준다는 것이다.

(Try[T] => Unit) => Unit

이제 => 를 뒤집고, Unit 을 () 로 표기해서 어떤 intuition 을 얻어보자.

(Try[T] => Unit) => Unit

Unit => (Unit => Try[T]) // reverse

() => (()=> Try[T]) // Unit -> ()

Try[T] // simplify

여기서 핵심은 () 는 사이드 이펙트를 위해 존재하므로 그 부분을 제거하면 타Future[T] 의 결과는 Try[T] 와 같다는 것이다.

Future[T]andTry[T]are dual

duality 란 Category Theory 에 의하면

Every statement, theorem, or definition in category theory has a dual which is essentially obtained by “reversing all the arrows”.

처음 시작 부분에서 이런 테이블을 봤을텐데, 여기서도 duality 관계가 나타난다.

One Many

Synchronous T/Try[T] Iterable[T]

Asynchronous Future[T] Observable[T]

그리고 지난시간에 이메일을 발송하는 코드에서 onComplete 를 몇 번 호출하던 콜백이 받는 Try[T] 는 동일하다는 것을 봤다. 이것은 Future[T] 가 Try[T] 를 돌려주고, 그 값이 일정하다는 사실을 말한다.

이렇게 생각할수도 있다. 콜백 f: Try[T] => Unit 을 넘기고 Try[T] 를 얻기 위해 asynchronous() 를 사용할 수 있고, Try[T] 를 얻기 전까지 ¸럭되는 synchronous 를 이용할 수도 있다는 식으로

def asynchronous(): Future[T]

def synchronous(): Try[T]

Iterable

Observable[T] 를 보기전에 synchronous data stream 인 Iterable[T] 를 좀 살펴보자.

trait Iterable[T] { def iterator(): iterator[T] }

trait Iterator[T] { def hasNext: Boolean; def next(): T }

while (hasNext) next() 처럼 사용할 수 있다.

그리고 Iterable[T] 를 위한 flatMap 도 정의되어 있다. 따라서 Iterable 은 모나드다.

def flatMap[B](f: A => Iterable[B]): Iterable[B]

이 Iterator 를 이용해서 디스크에서 파일을 읽는 코드를 작성하면

def ReadLinesFromDisk(path: String): iterator[String] = {

Source.fromFile(path).getLines()

}

val lines = ReadLinesFromDisk(path)

for (line <- lines) {

... DoWork(line) ... // latency

}

한 라인이 100K 로 어마어마하게 길다면 디스크를 읽기 전까지 기다려야할까? Future 처럼 비동°로 IO 연산을 수행하는 방법을 찾아보자. 이전과 좀 다른점은 지금은 컬렉션을 다루고 있다는 점이다.

이 문제를 해결하기 위해 컬렉션을 순회하는 trait 를 좀 살펴보자. 어떤 일을 해야 하는지 알아야하니까.

trait Iterable[T] {

def iterator(): Iterator[T]

}

trait Iterator[T] {

def hasNext: Boolean

def next(): T

}

Iterable, Iterator 을 좀 간략화 하면,

Iterable는()를 인자로 받아Iterator를 돌려주고Iterator는()를 인자로 받아Try[Option[T]]를 돌려준다

전체적으로 보면 () => (() => Try[Option[T]]) 다. 사이드이펙트로 예외를 돌려주거나, None 일수 있거나, 아니면 정상적인 값을 얻을 수 있다는 뜻이다.

타입이 좀 복잡한데, 아까 arrow => 를 뒤집었던 방법을 다시 사용해서 간단히 만들어 보자. 강의에서는 dualization trick 이라 부른다.

뒤집은 후에는 Try[Option[T]] 를 ¶해해 보자. 예외를 주거나, 아무 값도 주지 않거나(끝나거나), 값을 주거나.

() => (() => Try[Option[T]])

// reverse

(Try[Option[T]] => Unit) => Unit)

// simplify

( T => Unit, // Value

Throwable => Unit, // Exception

() => Unit // Nothing, Terminate

) => Unit

즉, 비동기로 컬렉션을 순회하기 위해서는 이런 작업을 처리해줄 무언가가 필요하다. 스칼라에서는 Observable, Observer, Subscription 이 그 일을 담당한다.

trait Observable[T] {

def Subscribe(observer: Observer[T]): Subscription

}

trait Observer[T] {

def onNext(value: T): Unit

def onError(error: Throwable): Unit

def OnCompleted(): Unit

}

trait Subscription {

def unsubscribe(): Unit

}

즉, Observable 에 Try[Option[T]] 에 따라 할일을 지정해 놓은 Observer 를 세팅하고, Subscription 을 얻은 뒤 이후에 필요에 의해 중단해야 하면 unsubscribe 를 호출하는 방식이다. 이는 작업하 대상이 컬렉션이므로 Future 와는 달리, 하나의 값이 아니라 무한한 값들을 얻어올 수 있기 때문.

Future vs Observable

초반에, 이 테이블을 다시 보면 Iterable 과 Observable 이 dual 이다.

One Many

Synchronous T/Try[T] Iterable[T]

Asynchronous Future[T] Observable[T]

그리고 이 테이블에 의하면, Future 와 Observable 을 비교해보면 one 과 many 가 의미하는 바를 type 으로 이해할 수 있다.

Observable[T] = (Try[Option[T]] => Unit) => Unit

Future[T] = (Try[T] => Unit) => Unit

타입을 보면 Future 는 Option 부분이 없지만 Observable 은 있다. 즉 Observable 은 아무런 값도 없다는 사실을 의미하는 타입 Option 을 이용해 종료시점 을 알려줄 수 있기 때문에 multiple values 를 처리할 수 있다.

concurrency 측면에선 어떨까? 타입을 살펴보면

object Future {

def apply[T](body: => T)

(implicit executor: ExecutionContext): Future[T]

}

trait Observable[T] {

def observeOn(scheduler: Scheduler): Observable[T]

}

Observable 의 경우엔 하나의 ExecutionContext 가 아니라 여러개를 가져야 하기 때문에 Scheduler 를 이용한다. 이 부분은 나중에 더 자세히 살펴보자.

Observable example

val ticks: Observable[Long] = Observable.interval(1 seconds)

val evens: Observable[Long] = ticks.filter(s => s % 2 == 0)

val bufs: Observable[Seq[Long]] = evens.buffer(2, 1)

val s = bufs.subscribe(b => println(b))

readLine()

s.unsubscribe

Observable 을 latency 를 지원하는 컬렉션으로 이해하면 쉽다. interval 을 이용해 간격을 지정하거나, 일반 컬렉션처럼 filter 도 사용할 수 있다. evens.buffer 는 그냥 버퍼링이라고 생각하면 된다. 버퍼 크기가 2인 것으로.

이런 것도 가능하다.

val xs = Observable.range(1, 10)

val ys = xs.map(x => x + 1)

xs 는 비동기 순회를 지원하는 컬렉션이다. filter, map, flatMap, take, zip 등 을 지원한다.

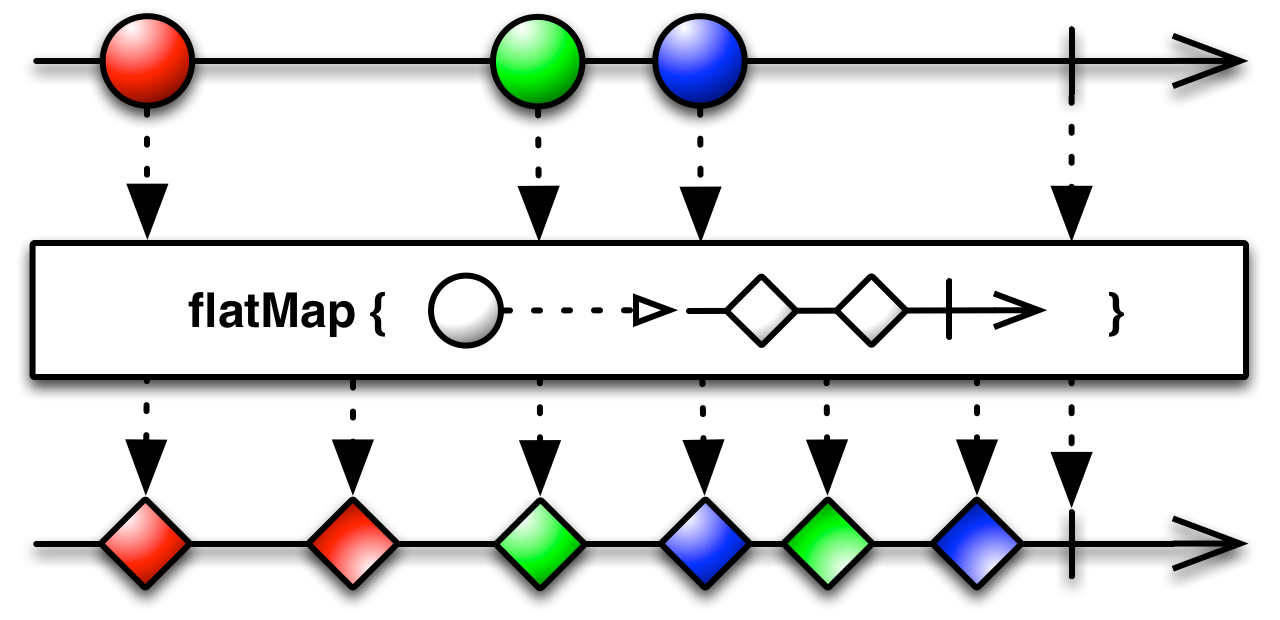

flatMap

색깔의 순서를 봐야할 필요가 있다. Observable 은 비동기 연산이기 때문에 순서가 좀 달라질 수 있다. 구현에도 그런 부분이 나타나 있는데 아래의 코드에서 flatten 이 의미하는 바는 non-deterministic merge 다.

def flatMap(f: T => Observable[S]): Observable[S] = {

map(f).flatten()

}

다른 코드도 좀 보면

val xs: Observable[Int] = Observable(3, 2, 1)

val yss: Observable[Observable[Int]] =

xs.map(x => Observable.Interval(x seconds).map(_ => x).take(2))

val zs: Observalble[Int] = yss.flatten()

위 코드는 x 초 후에 x 2개를 뱉는 Oberservable 을 만든 후 flatten 을 사용해 껍데기를 벗긴다. List(List(1, 2), List(3)).flatten 하면 List(1, 2, 3) 이 되듯이 Observable[Observable].flatten 도 Observable 을 만든다고 생각하면 쉽다.

Merge

예외나, 종료 등 어떤 이유에서든지 먼저 끝나는 Observable 에 의해 merge 가 종료된다는 점에 주의하자.

Concat

val xs: Observable[Int] = Observable(3, 2, 1)

val yss: Observable[Observable[Int]] =

xs.map(x => Observable.Interval(x seconds).map(_ => x).take(2))

val zs: Observalble[Int] = yss.concat

여기서 재밌는점은 yss 의 첫번째 원소인

Observable.Interval(3 seconds).map(_ => x).take(2)

가 끝나기 전까지 다른 원소들이 버퍼링 되므로 주의해야 한다는 점이다. marble diagram 으로 보면

Earthquakes example

def usgs(): Observable[EarthQuake] = { ... }

class EarthQuake {

...

def magnitude: Double

def location: GeoCoordinate

}

object Magnitude extends Enumeration {

def apply(magnitude: Double): Magnitude = { ... }

type Magnitude = Value

val Micro, Minor, Light, Moderate, Strong, Major, Great = Value

}

val major = quakes.

map(q => (q.location, Magnitude(q.magnitude))).

filter { case (loc, mag) => mag => Major }

major.subscribe({ case (loc, mag) =>

println($"Magnitude ${ msg } quake at ${ loc }")

})

이런식으로 사용할 수 있다. 더 실제 동작하는 코드는 여기로. 조금 복잡하다.

위치를 GeoCoordinate 로 받기 때문에, 해당 위치의 나라를 돌려준다든지 등으로 개선할 수 있다.

def reverseGeocode(g: GeoCoordinate): Future[Country] = { ... }

이 함수를 구현하면

val withCountry: Observable[Observable[EarthQuake, Country)]] =

usgs().map(q => {

val country: Future[Country] = reverseGeocode(q.location)

Objservable(country.map(country => (quake, country)))

})

// val merged: Observable[(EarthQuake, Country)] =

// withCountry.flatten()

val merged: Observable[(EarthQuake, Country)] = withCountry.concat()

여기서 머징하기 위해 flatten 이나 concat 을 사용할 수 있는데, 언급했듯이 어떤걸 쓰느냐에 따라 순서가 달라질 수 있다. 아래 그¼은 각각 flatten, concat 을 설명한다.

group by

def groupBy[K](keySelector: T => K): Observable[(K, Observable[T])]

즉 T 를 받아 키 K 를 만들고, 이것에 따라 Observable 을 그룹짓는다. 이걸 응용하면 나라별로 지진을 취합하는 것이 가능하다.

val byCountry: Observable[(Country, Observable[(EarthQuake, Country)]] =

merged.groupBy( case (q, c) => c }

이제 runningAverage 란 함수가 있다고 해 보자. Observable[Double] 을 받아 업데이트 후 Observable[Double] 을 돌려주는 함수. 그러면 runningAveragePerCountry 는 어떻게 구현할까?

val byCountry: Observable[(Country, Observable[(EarthQuake, Country)]]

def runningAverage(s: Observable[Double]): Observable[Double] =

{ ... }

val runningAveragePerCountry: Observable[(Country, Observable[Double])] =

byCountry.map { case (country, cqs) =>

(country, runningAverage(cqs.map(_._1.magnitude))

}

Subscription

지진 예제를 다시 가져오면, 더이상 관심 없을때 unsubscribe 를 호출할 수 있다.

val quakes: Observable[EarthQuake] = { ... }

val s: Subscription = quakes.Subscribe(...)

s.unsubscribe()

근데, 생각해보면 여러 곳에서 subscription 할 수 있다. UI °은 경우 그 수가 많을 것이다. 이 경우 unsubscribing 이 cancellation 을 의미하지 않는다. 왜냐하면 다른곳에서 subscribing 하고 있을 수 있기 때문이다.

타입을 좀 보면

trait Subscription {

def unsubscribe(): Unit

}

object Subscription {

def apply(unsubscribe: => Unit): Subscription

}

trait BooleanSubscription extends Subscription {

def isUnsubscribed: Boolean

}

trait CompositeSubscription extends BooleanSubscription {

def +=(s: Subscription): this.type

def -=(s: Subscription): this.type

}

trait MultipleAssignmentSubscription extends BooleanSubscription {

def subscription: Subscription

def subscription_=(that: Subscription): this.type

}

여기서 CompositeSubscription 은 컬렉션처럼 Subscription 을 추가하거나, 제거할 수 있고 unsubscribe 하면 나머지도 모두 취소 된다.

MultipleAssignmentSubscription 은 일종의 inner subscription 을 위한 프록시처럼 동작한다. 세팅하고, 교²´할 수 있지만, 항상 내부에는 동작하는 하나의 Subscription 이 있다.

import rx.lang.scala.subscriptions._

import rx.lang.scala.Subscription

val s = Subscription {

println("bye, bye")

}

s.unsubscribe()

s.unsubscribe() // buggy

이 경우 두번째 unsubscribe() 를 호출했을때 "bye, bye" 가 호출되지 않는다. 먼저 unsubscribe() 를 호출했기 때문이다.

직접 Subscription 을 구현할때는 다수의 스레드에서 저마다 unsubscribe() 를 호출할 수 있기 때문에 이 메소드는 idempotent 하게 구현되야 한다.

CompositeSubscription 을 이미 unsubscribe 했을땐, 새로운 Subscription 을 추가한다 하더라도 자동으로 unsubscribe 가 호출된다.

MultiAssignmentSubscription 의 경우에는 여러번 할당할 수 있으나, 단 하나의 Subscription 만 가리킨다. 따라서 다음 코드를 실행할 경우 b.unsubscribe 만 호출된다.

val a = Subscription { println("A") }

val b = Subscription { println("B") }

val m = MultiAssignmentSubscription()

multi.subscription = a

multi.subscription = b

multi.unsubscribe

CompositeSubscription 과 마찬가지로 이미 unsubscribe 되었다면, 할당되는 Subscription 도 자동으로 unsubscribe 된다.

CompositeSubscription 이나 MultiAssignment 를 연산을 공유하는 컨테이너라 볼 수 있겠는데, 그럼 여기서 내부의 것만 unsubscribe 하면 어떻게 될까? 당연히 외부의 MultiAssignment 나 Composite 는 알 길이 없으니 isUnsubscribe 는 false 가 된다.

Rx Stream

자주 보게 될 타입부터 소개하면

object Observable {

def apply[T](s: Observer[T] => Subscription): Oberservable[T]

}

trait Observable[T] {

def subscribe(observer: Observer[T]): Subscription

}

trait Observer[T] {

def onNext(value: T): Unit

def onError(error: Throwable): Unit

def OnCompleted(): Unit

}

trait Subscription {

def unsubscribe(): Unit

}

아무런 알림도 못받는 Observable 을 만드는 never 와, onError 를 호출하는 apply 를 구현해 보자.

def never(): Observable[Nothing] = Observable[Nothing](observer => {

Subscription {}

})

def apply[T](error: Throwable): Observable[T] =

Observable[T](observer => {

observer.onError(error)

Subscription {}

}

이제 이 함수들을 이용해 다양한 함수를 구현해 보자.

startWith

object Observable {

def apply[T](s: Observer[T] => Subscription): Oberservable[T]

}

def switchWith(ss: T*): Observable[T] = {

Observer[T](observer => {

for(s <- ss) observer onNext(s)

subscribe(observer)

}

}

filter

object Observable {

def apply[T](s: Observer[T] => Subscription): Oberservable[T]

}

def filter(p: T => Boolean): Observable[T] = {

Observable[T](observer => {

subscribe(

(t: T) => { if (p(t)) observer.onNext(t) },

(e: Throwable) => { observer.onError(e) },

() => { observer.onCompleted() }

)

})

}

map

object Observable {

def apply[T](s: Observer[T] => Subscription): Oberservable[T]

}

def map[S](f: T => S): Observable[S] = {

Observable[T](observer => {

subscribe(

(t: T) => { if (p(t)) observer.onNext(f(t)) },

(e: Throwable) => { observer.onError(e) },

() => { observer.onCompleted() }

)

})

}

그림을 잘 보면 input stream 으로 부터 값을 얻어 함수를 적용하고 output stream 으로 뱉는다. 구현도 마찬가지로 현재의 컨테이너인 Observable 로 부터 값을 얻었을때 함수를 적용하고 어떻게 넘겨줄지를 정의한다.

duality 관계인 Iterable 의 map 구현을 보면 더 명확히 알 수 있다.

def map[S](f: T => S): Iterable[S] = {

new Iterable[S] {

val it = this.iterator()

def iterator: Iterator[S] = new Iterator[S] {

def hasNext: Boolean = { it.hasNext }

def next(): S = { f(it.next()) }

}

}

}

Future to Observable

Future[T] 를 얻어 Observable[T] 로 바꿔보자. T 를 List[T] 로 바꾸듯이. 그럴려면 Subject 를 알아야 하는데, 이건 지난시간에 배운 Promise 비슷한 역할을 한다.

import scala.concurrent.ExecutionContext.Implicits.global

def race[T](left: Future[T], right: Future[T]): Future[T] = {

val p = Promise[T]()

left onComplete { p.tryComplete(_) }

right onComplete { p.tryComplete(_) }

p.future

}

Promise 로 부터 Future 를 얻고, Future.onComplete 에 콜백을 넘기면, 완료되었을때 Promise.complete 에 의해 호출된다. Promise 는 Future 를 위한 대리자? 프록시쯤으로 볼 수 있다.

Observable 과 Subject 도 비슷한 관계다.

코드로 이해해 보자.

val channel = PublishSubject[Int]()

val a = channel.subscribe(x => println("a: " + x))

val b = channel.subscribe(x => println("b: " + x))

channel.onNext(42)

a.unsubscribe()

channel.onNext(4711)

channel.onComplete()

val c = channel.subscribe(x => println("c: " + x))

channel.onNext(13)

Subject 는 일종의 채널이라 보면 된다. 위 코드에서 흥미로운 점은 onComplete (! 로 표시) 가 호출 된 뒤에 옵저버 c 를 Subject 에 추가했음에도 c 도 onComplete 가 호출된 것을 알고 있다는 사실이다.

val channel = ReplaySubject[Int]()

val a = channel.subscribe(x => println("a: " + x))

val b = channel.subscribe(x => println("b: " + x))

channel.onNext(42)

a.unsubscribe()

channel.onNext(4711)

channel.onComplete()

val c = channel.subscribe(x => println("c: " + x))

channel.onNext(13)

ReplaySubject 의 경우에는 c 에도 모든 데이터를 받는다. 이는 ReplaySubject 가 히스토리를 캐싱하고있기 때문이다.

다양한 종류의 Subject 를 그림으로 보면

Converting Future to Observable

object Observable {

def apply[T](f: Future[T]): Observable[T] = {

val as = AsyncSubject[T]()

f onComplete {

case Failure(e) => { as.onError(e) }

case Success(c) => { as.onNext(c); as.onCompleted() }

}

as

}

}

복잡하게 생각하지 말고 그냥 Promise 랑 비슷한 일을 한다고 이해면 쉽다.

Notifications

지난 시간에 Future 가 Try 를 이용하는걸 봤다. Future[Try[T] 처럼. Notification 도 이와 비슷하다. Observable[Notification[T]] 처럼 사용한다.

abstract class Try[+T]

case class Success[T](elem: T) extends Try[T]

case class Failure(t: Throwable) extends Try[Nothing]

abstract class Notification[+T]

case class OnNext[T](elem: T) extends Notification[T]

case class OnError(t: Throwable) extends Notification[Nothing]

case object onCompleted extends Notification[Nothing]

def materialize: Observable[Notification[T]] = { ... }

차이라면, 종료 를 알려주는 onCompleted 가 있다는 것이다. materialize 는 Observable[T] 를 감싸 Observable[Notification[T]] 로 만든다.

Blocking

권할만한 방법은 아니지만, 만약에, 만약에 블러킹이 필요하다면 이런식으로 코드를 작성할 수도 있다는 것 지난시간에 배웠다.

val f: Future[String] = { ... }

val text: String = Await.result(f, 10 seconds)

Observable 도 마찬가지다.

val xs: Observable[Long] = Observable.interval(1 seconds).take(5)

val ys: List[Long] = xs.toBlockingObservable.toList

println(ys)

// all Rx operators are non-blocking

val zs: Observable[Long] = xs.sum

val s: Long = zs.toBlockingObservable.single

Observable to Scalar Types

Observable 내에 있는 값들을 계산하기 위해 reduce 를 사용할 수 있다. fold 와 비슷하달까

def reduce(f: (T, T) => T): Observable[T]

재밌는 사실은 리턴타입이 원소가 Observable 을 돌려주기 때문에 Future 와 비슷다는 것이다.

Iterable to Observable

잘못된 구현을 먼저 보자.

def from[T](seq: Iterable[T]): Observable[T] =

Observable(o => {

seq.foreach(s => o.onNext(s)) // What if seq is infinite?

o.onCompleted // What if seq fails?

Subscription {}

})

이 구현의 문제점은, Iterable 이 무한하거나, 실패하면 어떻게 처리할지 전혀 고려하지 않았다는 것이다. 게다가 빈 Subscription 을 돌려주기 때문에, unsubscribe 할 수도 없다.

이 문제를 풀기 위해서는 scheduler 가 필요하다.

Scheduler

우선 돌아가는 코드를 만들기 전에 테스트 케이스부터 작성하자

// factory method

object Observable {

def apply[T](subscribe: Observer[T] => Subscription): Observable[T]

}

def from[T](seq: Iterable[T]): Observable[T] = { ... }

// infinite seq

def nats(): Iterable[Int] = new Iterable[Int] {

val i = -1

def iterator: Iterator[Int] = new Itertor[Int] {

def hasNext: Boolean = { true }

def next(): Int = { i += 1; i }

}

}

val infinite: Iterable[Int] = nats()

val subscription = from(infinite).subscribe(x => println(x))

subscription.unsubscribe()

만약 from 이 위에서 본 것처럼 구현되어 있다면 subscription.unsubscribe() 에 도달하지 못한다. 따라서 iteration 을 진행하는 것과는 다른 컨텍스트를 도입해 unsubscribe 를 호출해야 한다. 그래서 스케쥴러가 필요하다.

Future 에서는 ExecutionContext 가 있었지만, Observable 은 복수개의 컨텍스트를 조작해야 하므로 스케쥴러를 써야한다.

object Future[

def apply[T](body: => T)

(implicit executor: ExecutionContext): Future[T]

}

trait Observable[T] {

def observeOn(scheduler: Scheduler): Observable[T]

}

// Runnable == Java's Runnable

trait ExecutionContext {

def execute(runnable: Runnable): Unit

}

// '=> Unit' == Runnable

trait Scheduler {

def schedule(work: => Unit) Subsciption

}

// example

val scheduler = Scheduler.newThreadScheduler

val subscription = scheduler.schedule {

println("Hello World!")

}

Future 는 Runnable 을 취소할 수 있는 방법이 없지만, Scheduler 는 Subscription 을 리턴하기 때문에 취소할 수 있다. 그러나 일단 작업이 시작되면 취소할 수 있는 방법은 없다. 아래 예제를 보자

def from[T](seq: Iterable[T])

(implicit s: Scheduler): Observable[T] = {

Observable[T](o => {

s.schedule {

seq.foreach(x => observer.onNext(x))

observer.onCompleted()

}

}

}

onNext 가 호출되기 전, 아주 잠깐동안만 작업을 취소할 수 있는 기회가 있다. 다시 말해서, 이터레이션이 통채로 스케쥴링 되기 때문에 좀 별로라는 것이다. 매 이터레이션마다 취소할 기회가 있는 from 을 구현하고 싶다.

scheduler 의 다른 시그니쳐를 좀 보자.

trait Scheduler {

def schedule(work: => Unit): Subscription

def schedule(work: Scheduler => Subscription): Subscription

def schedule(work: (=> Unit) => Unit): Subscription

}

두번째 시그니쳐를 보자. schedule 함수가 하는 일이 Scheduler 를 받아 등록하고 Subscription 을 돌려주는 일이라면 그것 자체를 work 로 받고, 해당 work 에서 한번씩만 이터레이션 한다면 매 이터레이션에서 취소할 기회를 가질 수 있다.

이건 사실 세번째 시그니쳐와 동일한데 이유는 뒤에서 보겠다.

from 의 새로운 구현을 보면

def from[T](seq: Iterable[T])

(implicit) scheduler: Scheduler): Observable[T] = {

Observable[T](o => {

val it = seq.iterator()

scheduler.schedule(self => {

if (it.hasNext) { o.onNext(it.next()); self() }

else { o.onCompleted() }

}

}

}

으사양반 이게 무슨 개소리요!

조금 난해한데, it.hasNext 가 있어서 다음 이터레이션으로 넘어갈 수 있으면 self() 를 호출해 자기 자신을 스케쥴링다. 따라서 매 이터레이션마다 사용 가능한 Subscription 이 있으므로 취소할 수 있는 기회가 생긴다.

물론 Subscription 이 갱신되는데 어떻게 하나의 레퍼런스로 그게 가능하느냐 하는 질문이 나올 수 있는데, 우리는 이미 MultipleAssignmentSubscription 을 배웠다. schedule 함수의 내부를 보자.

def schedule(work: (=> Unit) => Unit): Subscription = {

val subs = new MultipleAssignmentSubscription()

schedule(scheduler => {

def loop(): Unit = {

subs.Subscription = scheduler.schedule {

work { loop() }

}

}

loop()

subs

})

subs

}

def from[T](seq: Iterable[T])

(implicit) scheduler: Scheduler): Observable[T] = {

Observable[T](o => {

val it = seq.iterator()

scheduler.schedule(self => {

if (it.hasNext) { o.onNext(it.next()); self() }

else { o.onCompleted() }

}

}

}

즉, self 가 바로 loop 다. 자기 자신을 스케쥴링하는 함수인데,

work -> loop -> work -> loop -> ... 을 반복하면서 더 이터레이션할 멤버가 없거나, unsubscribe 하기 전까지 재귀적으로 돈다.

Scheduler to Observable

돌려주는 값 없이 행위 그 자체만 보면, 스케쥴러 그 자체는 Observable[Unit] 에 대응된다.

object Observable {

def apply() (implicit s: Scheduler): Observable[Unit] = {

Observable(o => {

s.schedule(self => {

o.onNext(()); self

})

})

}

}

implicit val s = Scheduler.NewThreadScheduler

val ticks: Observable[Unit] = Observable()

이게 실제로 어떻게 동작하나 보면

object Observable {

def apply(s: Observer[T] => Subscription) = new Observable[T] {

def subscribe(o: Observer[T]): Subscription = { Magic(s(o)) }

}

}

val subs = Observable(o => F(o)).subscribe(observer)

// = conceptually

val subs = Magic(F(observer))

여기서 F 나 Magic 는 임의의 함수라 생각하면 된다. (그런게 있나보다 하자.)

이걸 왜 이야기하냐 하면 auto unsubscribe 가 가능하기 때문이다. 스케쥴링 하는 행위를 observable 로 변경할 수 있다면, 스케쥴링이 불가능할때 unsubscribe 하도록 만드는 것이다.

F 가 observer.onCompleted 나 observer.OnError 를 호출한다면, Magic 함수에 의해 자동으로 unsubscribe 가 호출된다. 이로인해 다음에 호출되는 onNext 는 아무런 영향도 미치지 않게 된다.

이럴 수 있는 이유는 Observable 을 생성하는 방식이 Rx Contract 을 만족하기 때문이다. (따라서 직접 Observable, Observer 를 만들지 말고 팩토리 메소드를 사용해야한다)

(onNext)*(onCompleted + onError)?

onNext 는 여러번 호출될 수 있으나 겹치지 않고, onCompleted 나 OnError 는 옵션이지만 (무한한 시퀀스가 존재하기때문) 호출된다면 둘 중 단 한개만, 단 한번 호출되야한다는 것이다. 아까 본 코드를 다시 나열해서 어떻게 그렇게 되나 살펴보자.

object Observable {

def apply() (implicit s: Scheduler): Observable[Unit] = {

Observable(o => {

s.schedule(self => {

o.onNext(()); self

})

})

}

}

def schedule(work: (=> Unit) => Unit): Subscription = {

val subs = new MultipleAssignmentSubscription()

schedule(scheduler => {

def loop(): Unit = {

subs.Subscription = scheduler.schedule {

work { loop() }

}

}

loop()

subs

})

subs

}

implicit val s = Scheduler.NewThreadScheduler

val ticks: Observable[Unit] = Observable()

ticks.subscribe(observer)

여기서 ticks.subscribe(observer) 를 계속 풀면

Observable({ o => scheduler.schedule {

self => o.onNext(()); self()

}}).subscribe(observer)

// unfold create

scheduler.schedule {

self => observer.onNext(()); self()

}

// unfold schedule

val m = new MultipleAssignmentSubscription()

schedule(scheduler => {

def loop(): Unit = {

m.Subscription = scheduler.schedule {

{ self => observer.onNext(()); self() }({ loop() })

}

}

loop()

m

})

// `self` is a continuation

val m = new MultipleAssignmentSubscription()

schedule(scheduler => {

def loop(): Unit = {

m.Subscription = scheduler.schedule {

{ observer.onNext(()); loop() }

}

}

loop()

m

})

// extract loop

val m = new MultipleAssignmentSubscription()

def loop(): Unit = {

m.Subscription = scheduler.schedule {

{ observer.onNext(()); loop() }

}

}

schedule(scheduler => {

loop()

m

})

// apply loop

schedule(scheduler => {

m.Subscription = scheduler.schedule {

{ observer.onNext(()); loop() }

}

m

})

즉 매 스케쥴링마다, subscription 을 갱신하고, 작업을 진행한뒤, 자기 자신을 다시 스케쥴링 한다.

Range

이렇게 응용할 수 있다.

implicit val scheduler: Scheduler = Scheduler.NewThreadScheduler

def range(start, Int, count: Int):

(implicit s: Scheduler) Observable[Int] = {

Observable(o => {

var i = 0

Observable().subscribe(u => {

if (i < count) { o.onNext(start + i); i += 1 }

else { o.onCompleted() }

})

})

}

val xs = range(1, 10)

xs.subscribe(x => println(x))

println("range out")

즉 Observable() 은 일종의 무한히 반복되는 스케쥴러고 여기에 액션을 추가해 원하는 작업을 해낼 수 있다. 그리고 작업이 완료되면 자동으로 unsubscribe 를 수행한다. 이제 무한히 긴 스트림을 Observable 로도 다룰 수 있게 되었다.

References

(1) Reactive Programming by Martin Ordersky

(2) http://reactivex.io/

(3) https://github.com/iirvine

comments powered by Disqus